Social Geist Theory Part II

ESSENTIAL DISCUSSION on the content from Part I.

Social Geist Theory Part I:

After over a week of being published, I can confidently say that my geist theory was received. As for whether or not it was received well, I have no idea. Needless to say, people had some interesting questions. For example, what exactly is geist theory in response to? I had to sit on this and dig deep into my mind in order to discover what this theory was subliminally in response to. Something I’ve alluded to in previous entries is how surprised I am by how coherent and replicative my ideas are across multiple entries. Meta-depression, systems of significance, LARPing, main character syndrome, meta by itself, and more. To discover what geist theory was responding to, I dove into my understanding of these concepts and themes – successfully. After all, what good is a theory if it doesn’t do anything?

I see theory as something that ought to challenge conventions. In the case of geist theory, though, I see it as more of a supplement. It’s a tool that describes some subtle mechanisms of contemporary social dynamics, and pulls on various pre-existing academic traditions.

That’s the thing about contemporary social dynamics. I think that they’re markedly different from social dynamics as we’ve understood them for the past… well, ever since sociology and psychology began trying to understand how people interact with their environments (social circles, too) with complex ideas.

Psychologists are notoriously schismed about which perspectives best explain human behavior. Does human behavior boil down to simple, quasi-deterministic conditioning, or as we would best understand it: training? A series of positive or negative reinforcements?

Or perhaps human behavior is best explained by the internal state of the individual human mind, and how that mind reacts to different situations and others’ minds.

As for sociology – or the science of explaining human society – I wouldn’t say that there are schisms as much as there’s a boiling pot of ideas that all try to explain hundreds of different things. Does human society as we know it begin from primitive religions? Did the sudden transition of human society from nomadic to sedentary ~10,000 years ago come from a sudden gene mutation? Or perhaps we just happened upon crop cultivation? Did grain cultivation cause the patriarchy? Does Big Grain still oppress us?

Between both psychology and sociology, there is a lot of uncertainty. A lot has happened in between the first cultivation of wheat and the dawn of modern capitalism. This in itself is a testament to just how much our species-wide circumstances change. Thus, what was once an explanation of fundamental human behavior can become antiquated in just a hundred-years’ time. Even Freud was once academically lucrative, if you will. A practice called trepanation – in which holes were drilled in the head to cure various ailments – was once considered a serious treatment.

What we now consider pseudo-science, or even just incorrect theories, were once the academic status quo. It seems as if the sciences cannot escape the shame of what was once normatively practiced in the past. What roughly happens now is: we develop new theories that discredit old ones, and arrogantly wag our fingers at our predecessors – even though we often owe them millions for their contributions.

“Contemporary social theory is always pretty schizoid-seeming because it violates a whole lot of constants.” Social Geist Theory

So, here’s the million-dollar question.

How do we view our current theories on human cognition, behavior, and social organization now as if we were looking back on them from the past, like we do with theories from years and years ago, that we can now so confidently critique?

Well, this requires crackpot innovation and zeitgeist-reading. It requires us to attempt to read between the lines as they’re being typed. I’m attempting this with geist theory.

Right now, the lines are being typed regarding 21st century society. It’s unlike anything we’ve seen before. All at once, the industrial world has never been more homogenous, yet so far apart. The more similar we all become, the more we take for granted our unique differences upon which social theories rely so greatly. We wear the same clothes, listen to the same songs, live in the same political machines (with little variance therein), and so much more. Sometimes it’s hard for us to see through these similarities from the top-down, like an observer. But horizontally, such as in inter-significant geistic groups, they become more clear. These meaningless similarities obscure meaningful similarities.

Geist theory attempts to explain how and when the meaningful similarities occur. It speaks to the intersection of a social group’s hidden peculiarities into a social group’s guiding principle — its Overarching Similarity. This theory assumes that there is such an invisible, guiding principle in modern social groups that is significantly differentiable from past social groups, and their guiding principles. It assumes that our desire to have these true, mutually significant groups – as I have cumulatively described them – goes above just the occurrence and phenomenon of relatability – or wanting to relate to others.

As a foundational idea, I think that geist theory can trickle down into more specific explanations of how contemporary social groups are unique; how they resemble unofficial guilds or miniature societies in response to our current cultural stagnation.

My good friend Jacob used a unique term last night: “convergence of circumstances.” We were discussing a theory about why creativity is so stagnated in modern society. Everything has become so singular that no matter which way we creatively turn away from the norm, we somewhat arrive at the same place within that singularity. It’s a little bit like the infinite staircase from Super Mario 64. No matter how long you run up the staircase, you will never reach the top – and that top might represent the creative viewpoint that we yearn for, from which we can look down at our environment and come up with a unique, creative perspective.

I think that this “convergence of circumstances” seamlessly translates into the realm of social theory at large, especially when you consider the general homogeneity I mentioned above. It’s as if we are, within the same singularity, trying to create our own worlds within which discernible and unique events occur. We’re yearning for a type of social creativity, like we’re graffitiing our meaningful social group on the big, Orwellian concrete wall that we call “society.” There’s nothing crazy about some guy in Pakistan wearing the same Nike shirt as me, even though he lives quite literally across the world. Yet, within a group of a few people, something as mundane as an inside joke about coffee, or a back condition, or some guy named John, can develop/acquire an almost mythical character within a contingency.

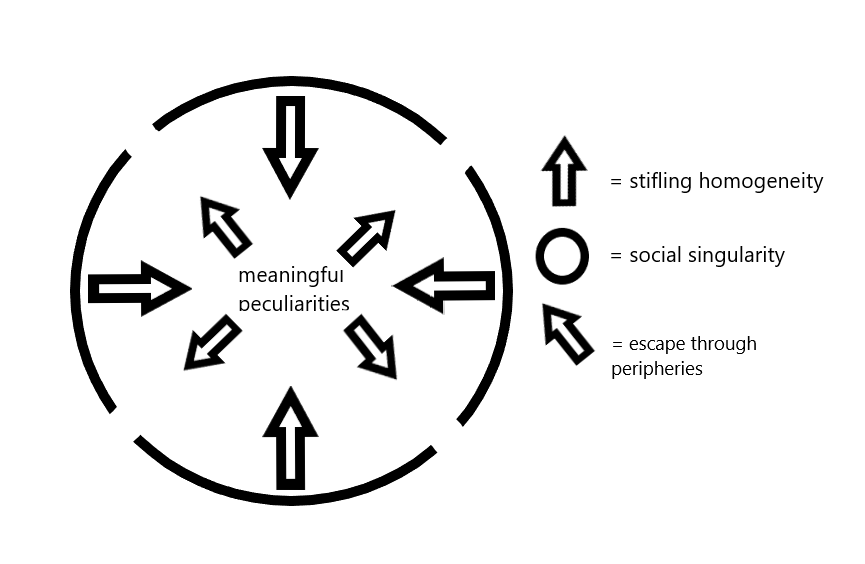

Therefore, in order to both produce and preserve meaningful similarities/peculiarities, and their mythical characteristics which oppose the mundane similarities of the social singularity, we create geistic entities that seek to escape through the peripheries of the social singularity.

As an aside, if you’ve ever wondered why the oddballs or misfits of society are so unique (often looking strange to us and having foreign behavior) and conglomerate, this might be why. In the search for true meaning, they have trotted through the peripheries in anticipation of escaping the social singularity. They represent the extremes of this meaning-searching demographic. This idea about the misfits isn’t anything new. However, I think that it fits well into geist theory.

These geistic entities are the manifestation of an authentic convergence of circumstances. If the suffocating social singularity clumps (converges) us together and creates a lump of crud, geistic entities press us together like gas in a chamber, to create energy and pressure.

We don’t, of course, typically create these entities consciously. One could argue that they develop naturally in opposition to the social singularity that denies us an authentic human experience, though I won’t comment on this just yet. It has its own complexities. For more context on the authentic human experience, do visit my entry on Meta-depression.

After a little bit of rambling, the moral of the story is this:

Geist theory is a means of explaining how contemporary social groups react and behave in relation to a social environment that’s hostile to meaning.

Through developing this, I hope to help the world understand what a true group is, and isn’t. How do we escape from the stifling social singularity? How do we develop extraordinary meaning in ordinary life? How do we restore a sense of the myth to our lives?

If you have any questions or comments, please leave them in the comment section below. The best way I can develop this is through feedback.

Thanks,

Black Bacon